The Wall Street Journal recently warned traders against treating stock market like a “slot machine”, they used quantum computing stocks as examples.

Leveraged funds tied to quantum computing firms like Rigetti and D-Wave have surged more than 700% this year with their names flashing across retail trading forums and financial dashboards.

Quantum computing is an extremely powerful technology that many still don’t understand, and as quantum stocks are back in the spotlight, the reason this time is different.

This time, it’s about the US government wanting a piece of these companies.

A new kind of government capitalism

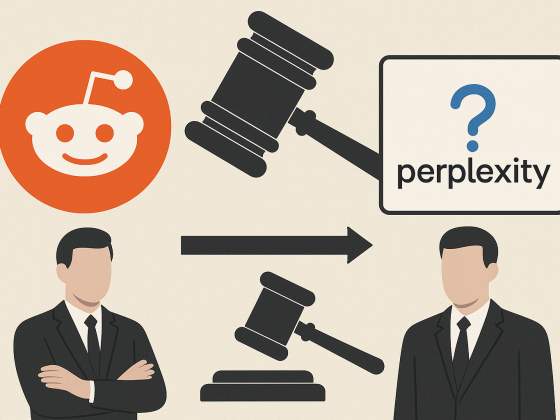

The Wall Street Journal just reported that the Trump administration is negotiating to take equity stakes in several quantum-computing firms, including IonQ, Rigetti Computing, D-Wave Quantum, and Quantum Computing Inc.

The Commerce Department, under Secretary Howard Lutnick, is offering at least $10 million in funding to each company through the restructured CHIPS Research and Development Office.

In exchange, Washington would receive partial ownership, warrants, or royalties, a modern version of industrial policy where the state becomes a shareholder in the technologies it funds.

This follows a similar precedent where in August, the government converted $9 billion in semiconductor grants into a roughly 10% equity stake in Intel, making it the chipmaker’s largest shareholder.

The Energy Department has also taken warrants in a lithium start-up and a rare-earth producer. The White House’s logic is that if taxpayers are financing critical industries, taxpayers should share in their upside.

But this new announcement is also a recognition that quantum computing is not a niche experiment but a cornerstone of national competitiveness.

The same way the CHIPS Act framed semiconductors as strategic, the current administration appears to be expanding that definition to include quantum technology.

The promise of quantum power

To understand why Washington is suddenly interested in ownership, it helps to grasp what makes quantum computing different.

Instead of using binary bits such as 1s and 0s, quantum computers rely on qubits, which can exist in multiple states at once. This enables them to process vast datasets and perform complex calculations exponentially faster than classical machines.

According to McKinsey’s report on the tech, the combined global quantum technology market, spanning computing, communication, and sensing, could reach $97 billion in annual revenue by 2035, up from about $4 billion today.

Quantum computing alone could account for as much as $72 billion, with applications in pharmaceuticals, materials science, logistics, and finance.

Boston Consulting Group projects total economic value creation between $450 billion and $850 billion by 2040.

The attraction is clear. Whoever leads in quantum computing could lead in artificial intelligence, energy discovery, and national security. The US is racing against China and the European Union to develop scalable, fault-tolerant systems that can run real-world applications.

Recently, Google announced that one of its quantum prototypes ran a computation 13,000 times faster than a top classical supercomputer. This is both a scientific breakthrough and a geopolitical signal.

From research to revenue

Until a year ago, most quantum companies were funded like research labs. But that’s changing rapidly.

Rigetti Computing, a California-based pioneer, announced $5.7 million in hardware orders for its nine-qubit Novera systems and a $5.8 million, three-year contract with the US Air Force Research Laboratory to advance quantum networking.

D-Wave Quantum has signed defense and logistics partnerships. Finland’s IQM raised $320 million last month to expand production of superconducting chips, while Maryland-based IonQ acquired the UK start-up Oxford Ionics for roughly $1.1 billion earlier this year.

Quantum stocks have followed the momentum. Rigetti shares have risen more than 135% in a month. D-Wave and IonQ have also more than doubled in 2025. Arqit Quantum soared 32% in a single week in October.

These moves can’t be driven purely by hype. There is a measurable shift from theoretical R&D to commercial adoption. Companies are finally selling systems, not just publishing papers.

Rigetti’s modular “chiplet” architecture, which links smaller qubit modules rather than relying on one massive chip, has shown 99.5% fidelity in testing, an engineering milestone in maintaining stability as systems scale.

These technical advances, coupled with credible revenue streams and government contracts, are giving investors reasons to take notice.

The market’s dangerous enthusiasm

In reality, markets rarely distinguish between progress and perfection. As the WSJ reported earlier this month, leveraged single-stock ETFs that track these quantum companies have returned up to 1,000% since March.

The catch is that these instruments are meant for professional traders holding positions for hours, not months. Behind the glittering numbers are financing costs that can reach 15% to 20% annually, hidden in swap spreads and volatility premiums.

The surge of speculative quantum stocks echoes past technology booms, from dot-coms to solar energy. The danger lies in mistaking government endorsement for guaranteed success.

While some companies may indeed become the next Nvidia of quantum computing, many will not survive the transition from experimental physics to commercial scale. McKinsey estimates that most meaningful applications are still three to five years away.

For investors, this is a market defined by both extraordinary potential and extreme uncertainty. The science is real, but the timeline is long. Quantum hardware remains fragile, with error correction still the defining challenge.

Betting on these firms today means betting on who will cross that technical threshold first.

The birth of the quantum economy

The US government’s decision to take equity stakes marks the beginning of a new era of state-backed innovation. Unlike past subsidy programs, Washington is now positioning itself as an investor, and not just a funder.

This indicates a strong willingness to accept risk and share reward, to treat technology not as a public good alone but as a strategic asset.

But it also raises complex questions. Should the government influence board decisions in companies it partially owns? What happens when national priorities conflict with shareholder interests?

These debates will intensify as the state extends its reach into sectors like AI, advanced materials, and energy storage.

Nevertheless, the US is not retreating from markets. It is trying to “reengineer” them. The government’s entry into quantum computing represents an effort to anchor critical innovation within national borders, to ensure that the next computing revolution is American-led.

Investors should see this not as a bubble but as the early architecture of a new industrial framework. Public money is flowing toward companies that blend scientific credibility with commercial readiness.

Those that can convert contracts into scalable systems will define the next generation of computing power and, by extension, the next phase of global growth.

In physics, a quantum system exists in multiple states until it is observed. The same is true for this market. Quantum computing sits in a superposition of promise and peril. The observation, it seems, is coming soon enough.

The post Quantum computing is the next big thing and US government wants in appeared first on Invezz